Zooplankton of the Great Lakes Homepage

Cladoceran: Daphnia retrocurva

Site Created By: Erin L. Murchie

Site Created By: Erin L. Murchie

|

Classification and Taxonomic History

Kingdom - Animalia S.A. Forbes first described this species in 1882. D. retrocurva was then considered a variety of the previously described D. kahlbergensis after Herrick and Birge (1884 and 1893, respectively) noticed a similarity to this species (Balcer et al., 1984). Richard (1896) and Sars (1915) placed D. retrocurva into a new genus, Hyalodaphnia, created for all Daphnia lacking an ocellus. By 1918, however, the new genus became obsolete and the species was once again reclassified as D. retrocurva (Balcer et al., 1984). Due to variations in helmet shape, Woltereck (1932) reclassified D. retrocurva as D. pulex parapulex but was met with disagreement from many other researchers and by 1946, Brooks reverted to back to this species' original name, Daphnia retrocurva (Balcer et al., 1984). . Figure 1. Daphnia retrocurva displaying the characteristic recurved helmet and absent ocellus. Distribution D. retrocurva is found primarily in formerly glaciated in northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. Both smaller inland lakes as well as all five Great Lakes contain D. retrocurva, with highest densities being found in the summers (Balcer et al., 1984). D. retrocurva is found primarily near shore in the Great Lakes and in the open water when densities are highest. With the exception of Puget Sound, D. retrocurva is generally not found West of the Rocky Mountains (Balcer et al., 1984). Feeding Ecology D. retrocurva feed on a mix of algae, protozoa, bacteria and detritus through use of a filter feeding system. A constant water current is produced from movements of the thoracic legs which direct food items toward the mouthparts and into the intestine (Pennack, 1978). It is thought that D. retrocurva is not a selective feeder, however when food items are rejected, possibly due to size, they are pushed out using the post abdominal claw (Pennack, 1978).

Figure 4. Eggs of D. retrocurva early in development in the brood chamber.

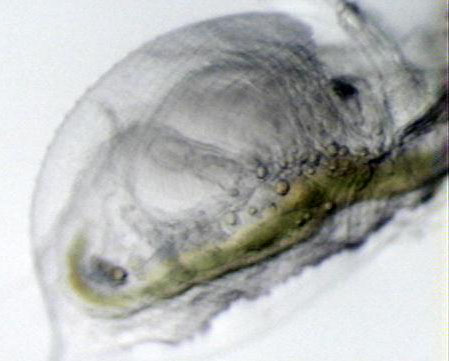

Figure 6. Highly developed young D. retrocurva still within the brood chamber. |

|

Anatomy Like others of the Daphnia genus, D. retrocurva has a body contained by a bi-valve carapace (Figure 2) and possesses 5 sets of trunk appendages used for feeding and gas exchange (Ward and Whipple, 1959). The head has a round shape which tapers into a rostrum along the ventral margin, possesses a large compound eye and the first and second antennae. The small first antennae (antennule) contain olfactory sensory organs while the large second antennae serve as swimming appendages (Ward and Whipple, 1959). The heart is located dorsally and superior to the brood pouch while the anus and post abdominal claw are located at the posterior end of the body (Barnes, 1980). D. retrocurva can be distinguished from other members of the Daphnia genus primarily by the absence of an ocellus (Ward and Whipple, 1959), and the presence of a recurved helmet, although some individuals may lack a helmet formation (Figure 3) (Balcer et al., 1984). Another defining feature of D. retrocurva is the enlarged middle pectin of the post abdominal claw, which can only be seen at higher magnification (Balcer et al., 1984). Finally, D. retrocurva length (including helmet) has been reported to be 1.3-1.8 mm for females and 1.0 mm for males (Balcer et al., 1984).

Figure 2. Notice the textured pattern of the D. retrocurva carapace.

Figure 3. D. retrocurva lacking the typical recurved helmet. Growth and Reproduction For the majority of the time, D. retrocurva is parthenogenic, producing only 2N females from 2N females. Eggs are released into the brood chamber where they develop into young that look very similar to the adults (Figures 4, 5, and 6) and then are expelled from the brood chamber and carapace (Figure 7) (Pennack, 1978). Sexual reproduction will occur after a stimulus of unfavorable conditions such as low food, crowding, or drying up of water (Ward and Whipple, 1959). Sexual D. retrocurva often occur between late August and November and exhibit highly recurved helmets (Balcer et al., 1984). Male eggs, also 2N are produced and hatched and 1N female eggs are then produced shortly after. The 1N eggs are then fertilized by 1N sperm produced by the previously hatched males. The result is the development of of 2N eggs within a hard protective case (ephippium) which is resistant to desiccation and damage (Ward and Whipple, 1978). Hatching of diapause (or resting) eggs within the ephippium may depend on temperature , however, there does appear to be a wide time range for hatching (Balcer et al., 1984).

Figure 5. Further development of eggs/young D. retrocurva in the brood chamber. The compound eye is visible on the left-most embryo.

Figure 7. The newly born D. retrocurva looks like a miniture version of it's mother. |

| Works Cited Balcer, M. D., N. L. Korda, and S. I. Dodson. 1984. Zooplankton of the Great Lakes: A Guide to the Identification and Ecology of the Common Crustacean Species. University of Wisconsin Pres. Madison, Wisconsin. Pg. 62-64. Barnes, R. D. 1980. Invertebrate Zoology Fourth Edition. Saunders College/Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Pg 678-679 Pennak, R. W. 1978. Fresh-Water Invertebrates of the United

States Second Edition. John Wiley and Sons, New York. Pg. 350-359. |